Two US electric utilities recently declared something remarkable: It’s cheaper to tear down their coal plants and build renewable-energy plants than to keep the old boilers running. For the utilities, the goal is now to retire their coal plants and exceed the economy-wide climate targets set in the Paris Agreement: an 80% reduction of carbon emissions from 2005 levels by 2050.

It’s a surprising move by two (primarily) coal-powered utilities in the American West, but get ready for more. Economics, and politics, are fast converging on a consensus. Committing to a 100% carbon-free goal, even before we quite know how to reach it, is good for business.

The first to make the announcement was Xcel Energy, a utility serving 3.6 million people in eight states from Minnesota to New Mexico. On Dec. 4, the company said it would hit an 80% reduction target by 2030, and eliminate all carbon emissions from its power plants by 2050. Two days later, Colorado’s Platte River Power Authority (an Xcel competitor) approved its own goal of 100% carbon-free energy by 2030.

Jason Frisbie, general manager of Platte River Power Authority, said it was just an admission of economic realities, not a political statement. “This whole thing started because the board wanted to recognize the shift that has already been taking place in the business for several years,” he told a local newspaper. Cities buying its electricity were demanding clean energy, and the price of renewables had tumbled below even the cheapest fossil fuels.

Costly coal

Although the announcements came in quick succession, they’ve been a long time coming, says Mark Dyson of the energy nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute. At least 90 cities have declared their intention to adopt 100% renewable energy goals. Utilities can accept this, or risk losing their biggest customers.

Two major defections recently drove home the point. In Boulder, Colorado, the city council voted on Dec. 4 (the same day Xcel made its announcement) to leave the utility to pursue its own 100% renewable electricity generation two decades earlier than Xcel. In Silicon Valley, San Jose left the utility PG&E this year to offer a 100% renewable option from San Jose Clean Energy. (PG&E is only delivering 80%.)

After years of hedging their bets, utilities can’t ignore the numbers anymore. Last week, PacifiCorp, which relies on coal for 59% of its fuel, said it’s more expensive to run 13 of its 22 coal units than to retire them and switch to renewables. The company estimated it could save money by shutting down 60% of its units by 2022, an assessment largely in line with the Sierra Club’s calculations. Globally, at least 42% of the world’s coal power stations are operating at a loss, estimates the research nonprofit Carbon Tracker.

Dyson says it’s just a matter of time before more utilities across the US reach the same decision to replace old coal with “crazy cheap” new renewables. In Colorado, bidders are selling wind for as little as $12 per megawatt hour (MWh) and solar for $23 per MWh. Even after adding batteries to solar farms to keep supplying power into the evening, the cost rises to just $30 per MWh. That’s before income tax credits of 30% for new renewables built by 2023. Those prices are well below the average US price of nuclear ($105/MWh), coal ($67/MWh), and even low-cost natural gas ($39/MWh), according to Ravi Manghani of energy research firm Wood Mackenzie.

Steel for fuel

With prices so low, investing in new renewable-energy infrastructure instead of fuel is a no-brainer. In fact, that’s the basis of Xcel’s new business model: “steel for fuel,” with steel meaning new wind turbines and solar arrays. Xcel, like most vertically integrated utilities, is a regulated monopoly. A state commission sets customers’ prices so the utility can earn a reasonable rate of return on what it builds without overcharging. More stuff on the ground equals more money. In the case of renewables, argues Xcel CEO Ben Fowke, “everybody benefits.” Xcel earns money on the new “steel” and customers get lower prices far into the future.

More utilities are following its lead. The Southern Company’s CEO said in April that the utility will be “low to no carbon” by 2050. Earlier this year, New Mexico utility PNM said (with no publicity) it will exit all coal generation by 2031. In October, northern Indiana’s Public Service Company said it will save $4 billion by replacing all coal generation with renewables by 2028.

Yet some are still fighting to make coal great again. In the same week of Xcel’s announcement, Wyoming’s Black Hills utility proposed buying an existing coal power plant as the cheapest option with “long-term price-stability,” a characterization that left some analysts scratching their heads (jobs may have something to do with it). Meanwhile the Trump administration is rolling back environmental rules such as the Clean Power Plan and promoting a Coal FIRST initiative to keep coal plants open. But Moody’s Analytics, a financial analysis firm, said these actions “will not materially derail decarbonization trends.”

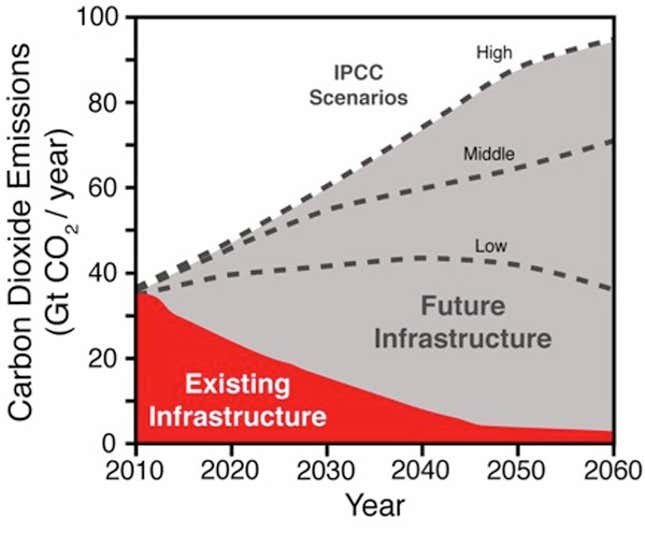

Built-in climate catastrophe

Accelerating those trends is critical to avert catastrophic climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions have already baked at least 2°F into the climate, and just 15 years remain to avoid another one-degree rise. Stopping the construction of new, long-lived power plants that emit carbon for decades is the only way to avoid this. ”Most warming anticipated this century is from infrastructure yet to be constructed,” writes Ken Caldeira, a climate scientist at Stanford University.

For now, the grid is not quite ready for 100% renewables. Far more storage will need to come online. High-voltage transmission lines must ferry energy from (often remote) wind and solar arrays to their final, urban destinations. With utilities set to approach 80% renewables in the next decade, the last 20% of carbon-free electricity will be the hardest to achieve.

“Technical options exist but it does get costly,” says Tom Wilson, a renewable-energy expert at the Electric Power Research Institute. Right now, the only cost-effective commercial options running at scale are nuclear reactors (very pricey) and large hydroelectric facilities (hard to site new ones). While geothermal, carbon sequestration, revolutionary batteries, and experimental small reactors are among future cost-effective possibilities, utilities are betting the right solutions will come on time. “If you have the vision, and the need to get there, sometimes the technology shows up,” says Wilson.