Lead Edge Capital

Why We Like SaaS Businesses

*This post was originally included in our Quarterly Letter to our LPs in Q4 2012, before Concur had been acquired by SAP for $8.3B.

*

During our numerous meetings with our Limited Partners, many often ask us two questions: “What is it that you like most about SaaS companies?” and “How do we value SaaS companies?” In regards to the first question we like SaaS businesses for several reasons.

First, we like SaaS companies’ inherent annuity streams. In other words, SaaS companies acquire customers that look like life insurance policies, whereby each new customer presents a long-term recurring revenue opportunity. Since the contracts are annual subscriptions, companies are often more concerned with farming the customer over the long run than they are with negotiating the initial contract. A good sales team selling a product that works should be able to generate customer retention rates above 90% and revenue retention at or above 100%.

Second, SaaS companies tend to have low churn and high renewal rates, resulting in high customer lifetime values. This occurs for two primary reasons. First, SaaS companies are built for strong customer service. Unlike traditional software vendors, constantly searching for the next big win, SaaS companies rely heavily on upselling and customer renewals for survival. Thereby, poor customer service is not an option for SaaS companies. Also, many SaaS apps require widespread user adoption throughout the enterprise, which requires training and behavioral changes. The potential for “employee disruption” doesn’t justify changing SaaS apps simply to save a few bucks.

The third reason we like SaaS companies are high gross margins. Gross margins typically range from 60% to more than 80% with the primary COGS being network and delivery costs, as well as services personnel (e.g., maintenance, training, implementation, etc.). As the customer base matures and the company reaches scale, most SaaS companies should achieve gross margins in the 75%–80% range, depending on the level of professional services required to deploy the solutions.

The fourth and final reason we like SaaS companies is they have much more efficient R&D spend than traditional licensed software companies. In general, R&D expenses (as measured as a percent of revenue) for public SaaS co’s are lower than traditional licensed software companies. Unlike licensed software vendors, SaaS companies are not required to support multiple technology stacks (i.e., operating systems, Web servers, databases, etc.) or a variety of hardware platforms. Additionally, SaaS solutions are typically version-less (all customers are on the same version) thereby enabling critical R&D dollars of the organization to focus on the next version and innovation (as opposed to supporting previously written releases). Some analysts estimate that legacy licensed software vendors spend as much as 80% of their R&D expenditures on supporting old products. Analysts believe the normal range of R&D for a mature SaaS company is 7%–12% of revenue, compared to 15%–25% for a traditional licensed software company.

The second question investors often ask us is: “how do we value SaaS companies?” In order to understand how to value a SaaS company, one needs to understand a few important definitions.

- Bookings: With a traditional enterprise software company, most software that is booked in a quarter is recognized in the same quarter. Thus, software revenue and software bookings (i.e., new contracts) are essentially the same. However, for a pure SaaS company, evaluating the income statement is like looking in the rearview mirror. Typically, software bookings translate into revenue multiple quarters down the road. Thus, bookings are a better indicator of future performance than revenue.

- Free Cash Flow (FCF): Free cash flow is defined as cash flow from operations less capital expenditures. Since SaaS vendors host applications for the customers, capital expenditures are an ongoing cost of business and important to monitor. In many instances, free cash flow is significantly more than operating profits. There are two important things that can dramatically affect cash flow in SaaS companies. First is the contract length, in that customer contracts can vary from monthly arrangements to multi-year upfront commitments, which can have a material impact on cash flow and deferred revenue. The second is the cash collection policy, in that some companies bill 30 days in advance, some collect one year up front and some collect multiple years up front. Many vendors have a combination of all three. All can have material impacts on cash flows.

In short, valuing SaaS companies is a challenge, and both investors and analysts have many different opinions on how it should be done. Some people focus on earnings (GAAP and/or non-GAAP) and free cash flow, while others prefer to focus on enterprise value to revenue. While some investors believe enterprise value to-revenue multiples are an unsatisfactory method of valuing a company, it is clear that in the absence of meaningful profitability, an avenue outside of earnings must be taken. Where earnings are absent due to failed business models, it could well be argued that the revenues generated by a firm may well be worthless since there is no clear path to profitability or at least positive cash generation. In the case of SaaS companies, earnings bases are typically negative, based not upon poor financial structures, but rather upon high rates of reinvestment made to support the accelerated growth of their valuable high-margin recurring revenue base. Given the highly recurring, low churn revenue base, it is fairly simple to calculate the net present value of the installed customer base assuming the company was operating under a steady-state condition (i.e., not investing for new growth). Over the long run, the revenue bases should evolve to support strong earnings bases due to significant operating leverage.

This leverage comes primarily from sales & marketing, which is universally the largest drag to operating margins and the largest expense as a percentage of sales. It’s important to understand that within the software industry the sales and marketing function is often the most important and most strategic component for growth. For SaaS companies, this expense is exaggerated, as costs are recognized up front while revenue is deferred over multiple periods. As a result, assessing the performance for a sales force is challenging while many of the old rules don’t apply, thus determining the right sales force size can be difficult using only GAAP or non-GAAP metrics. We use several metrics to measure the performance of sales and marketing effectiveness.

- Magic Number: The magic number is a metric that provides insight into the effectiveness of sales and marketing spend in the context of recurring revenue growth. This number provides a high-level view of a combination of factors, including market saturation and competitiveness, sales force effectiveness and retention, and up-sell and cross-sell strength of existing customers. The magic number is calculated by dividing new annualized quarterly revenue by S&M spend in the quarter. The key insight is that if the magic number is greater than .75, it makes sense to invest in growth because the business is primed to leverage spend. This number can also help alert management and investors as to when something may not be working. A number between 0.00 and 0.75 should alert a company to take a closer look at their internal process and market position. It could mean that market saturation is high, competition is challenging on price, sales force is ineffective, or the market isn’t growing fast enough; all of which may justify a reduction in spending or restructuring of the sales force.

- CAC Ratio: The CAC ratio is similar to the magic number but provides insight into the ultimate profitability of S&M investments. It is calculated by multiplying new annualized quarterly revenue by gross profit and dividing by S&M expense for the quarter. A CAC ratio of .5 shows that half of the investment is paid back within a year, and assuming low churn, paid back in full in two years.

- Cost to acquire a customer – CAC: This is calculated by taking sales and marketing spend and dividing by the new customers added in the quarter. This gives us a sense of how acquisition costs trend over time.

- % Attainment: This represents the percentage of total sales capacity that is actually generated by sales reps. It gives us the ability to benchmark against other companies and determine how realistic our sales force productivity model is.

- Sales Performance (MRR): Defined as how much monthly recurring revenue a sales rep on average is bringing into the company. If we multiple this number by 12, we get annualized recurring revenue which is a percentage of sales quota.

One way to understand the financial leverage, is to use an example of a company that is a microcosm of the sector itself. To that end, we’ve decided to examine Concur Technologies, a provider of SaaS based expense management and travel solutions. The company has been public since 1998, and currently trades at about the median multiple for the SaaS comp set we discuss below.

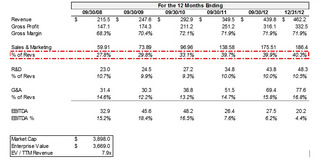

Concur’s financials are featured below:

Upon closer review of these financials, a few things should stand out. First, it is clear that the largest operating expense line item is Sales and Marketing at 40.3% of sales vs. 16.8% for G&A and 10.5% for R&D. Concur is spending over $186 million dollars on discretionary sales and marketing today, in order to win long term, high gross margin contracts with its customers in the future. Substantially all of Concur’s revenues are recurring, and the company has a 95% customer renewal rate. So, what might happen if Concur pulled back its spend?

Concur’s financials end up looking significantly different if they pull back the throttle on sales and marketing spend. Due to the low 5% annual churn rate, 95% of customer revenue would continue to recur each year, but the company could dramatically increase its profitability. In some ways, this could be thought of as an annuity contract with 72% gross margins that would decay at a rate of 5% per year. The stream of cash flows is indeed highly predictable.

Concur can also make a good acquisition target, given the recurring nature of its revenue, and historically high retention rates. Key points for a potential acquisition include:

- Large acquirers (i.e. IBM, Adobe, Oracle, etc.) can acquire Concur and plug the company into their massive sales forces, increasing sales productivity

- Concur currently has ~400 salespeople

- Oracle has 30,000 salespeople

- Large acquirers can cut duplicative administrative costs while maintaining recurring revenue base, dropping savings to the bottom line

In our opinion, it is appropriate to apply a revenue-based multiple in attempting to determine a fair market value for these companies. Given gross margin structures and significant over investment in sales & marketing to gain recurring revenue customer contracts, we think it’s obvious that once revenue growth rates moderate, considerable profitability should be achievable. Over the long term, SaaS companies of course will revert to earnings-based and free cash flow valuations as their operating models mature. With blended gross margins already routinely coming in at 70-80% or greater, operating margins should mature to routine levels of 25-30% or greater while exhibiting strong stability due to the companies’ highly recurring revenue base. Under such a scenario, a premium earnings multiple should be justifiable for SaaS companies to account for the strong predictability and visibility the companies offer investors. In the interim though, there is no clear answer as to what is the appropriate revenue multiple for SaaS companies, as industry multiples have had large swings, and as investor sentiment in the broader market has varied. At the best of times, multiples of 6-8x trailing revenues were common, with some capable of reaching higher into a 10x or better range. While in a soft market, multiples for many have fallen to a 3-4x range for trailing revenues, with the most pressured companies (with negative earnings bases and short track records) proving capable of trading below 2x trailing revenues. The chart below depicts the revenue multiples of 14 SaaS companies on a semi-annual basis since 2008.

Based upon this data, it is clear that there is a trend here and that SaaS companies have been valued off of high revenue multiples for a long time, and their multiple expansion and contraction has roughly tracked the broader financial markets.

Overall, our intent here was not to make a justification of SaaS company valuations, but rather to highlight why SaaS businesses are good businesses, why they often trade on multiples of revenue and why they make good potential acquisition targets. In a nutshell, these businesses have high gross margins, mostly recurring revenue, and the potential to be very profitable. We believe that our strategy of investing in these businesses in the private markets, while using structure to mitigate downside risk, is a sound path to generating outsized risk adjusted returns moving forward. Most importantly, we hope that this piece has helped many of our LPs who are less familiar with the software sector understand why we believe these businesses are attractive.